An Interdisciplinary Approach to Archeology and Art on a Caribbean Plantation

Article co-authored with Dr. Matthew Reilly for the Society of Historical Archeology (SHA) Fall Newsletter

(Vol. 54, No. 3: pg 36-40)

Abstract: Despite a long tradition of plantation archaeology in the Caribbean, there has been

little engagement between archaeologists in contemporary Caribbean artists who similarly think

with and through material culture. We here outline an interdisciplinary project that incorporates

archaeological and artistic practice as a lens through which to understand the history of

plantation slavery in Barbados and the significance of its material vestiges in the present.

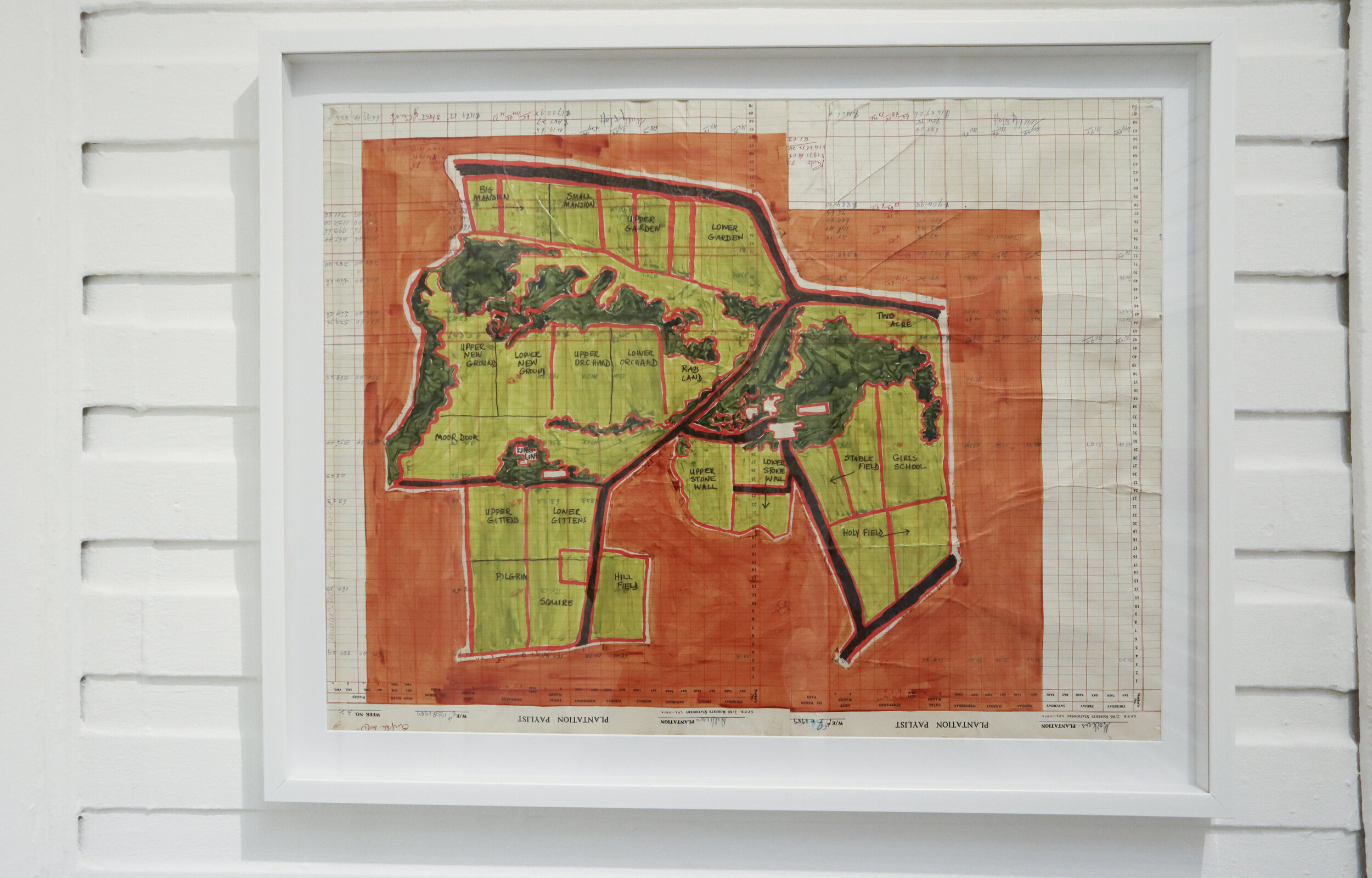

Figure 1: Aerial view, Walkers Dairy Farm, St. George, Barbados, W.I. Photo credit: Paul Davis.

Bridging the fields of archaeology and visual art, ongoing work at Walkers Dairy Farm, St. George, Barbados (Figure 1) is exploring the material past of a sugar plantation and how that past weighs on the contemporary landscape in the 21st-century Caribbean. The methods briefly summarized here are a marked attempt to combine traditional archaeological analyses of plantation life with the production of visual art to create an interdisciplinary lens through which to understand and represent changes unfolding on the Barbadian landscape beginning roughly 400 years ago. Of the many aims and research questions of the project, we here focus on two: (1) How can archaeological methods be used to explore changes to the plantation landscape from the onset of the sugar and slavery system into the 21st century? (2) How does the intersection of artistic and archaeological methodologies shift the way in which plantation spaces are studied?

Archaeological studies of Barbadian plantations have a long history, dating back to pioneering investigations by Jerome Handler and Frederick Lange (1978). With few features associated with enslaved populations visible on the Barbadian landscape, our study is partly inspired by previous attempts to locate significant sites of the African Diaspora that had been erased after centuries of intensive sugar production across the island (Handler et al. 1989; Armstrong and Reilly 2014). Field surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019, including over 100 systematic shovel test pits, targeted fields with topography, positioning, or historic names that hint at the location of the village for enslaved plantation inhabitants in centuries past. Walkers, which now operates as a dairy farm, was initially established as Willoughby’s in the 1660s. Likely established by William Willoughby, who served as Governor of Barbados from 1667 to 1673, the property is an ideal context in which to explore how plantation space was organized to maximize profit and implement a brutal regime of race-based slavery. As Governor of the island during a critical period in the midst of what is often referred to as the “sugar revolution”, Willoughby inaugerated the sugar and slavery system on his own property as he oversaw the functioning of what was at the time England’s most profitable colony.

Building on previous investigations conducted by Reilly (2019) surrounding race and class on the margins of a Barbadian plantation, our surveys, in part, seek to understand changes in spatial organization over the centuries in which sugar was grown on what was once an estate of over 300 acres. Specific fields were selected for shovel test pit surveys (Figure 2) based on names that might indicate features or former functions, density of surface scatters of artifacts, and historical knowledge of where planters chose to place villages for the enslaved. Historic maps include field names like “Mansion”, “Stable Field”, and “New Ground”. Based on the fact that many villages for the enslaved, or spaces allocated for their provision crops, were located in fields called “Negro Yard” (Handler 2002), it’s possible that “New Ground” was the location of a new village for the enslaved during a period of reorganization or a village or provision plot for free Afro-Barbadian laborers after Emancipation. Such fields, potentially once home to the enslaved, the residence of Governor Willoughby, or the plantation’s stables, are now used for cattle grazing, bearing no visible indication of their use in centuries past.

Figure 2: Project team members from the City College of New York excavate a test pit in a field north of the windmill, July 2019. Photo credit: Matthew C. Reilly.

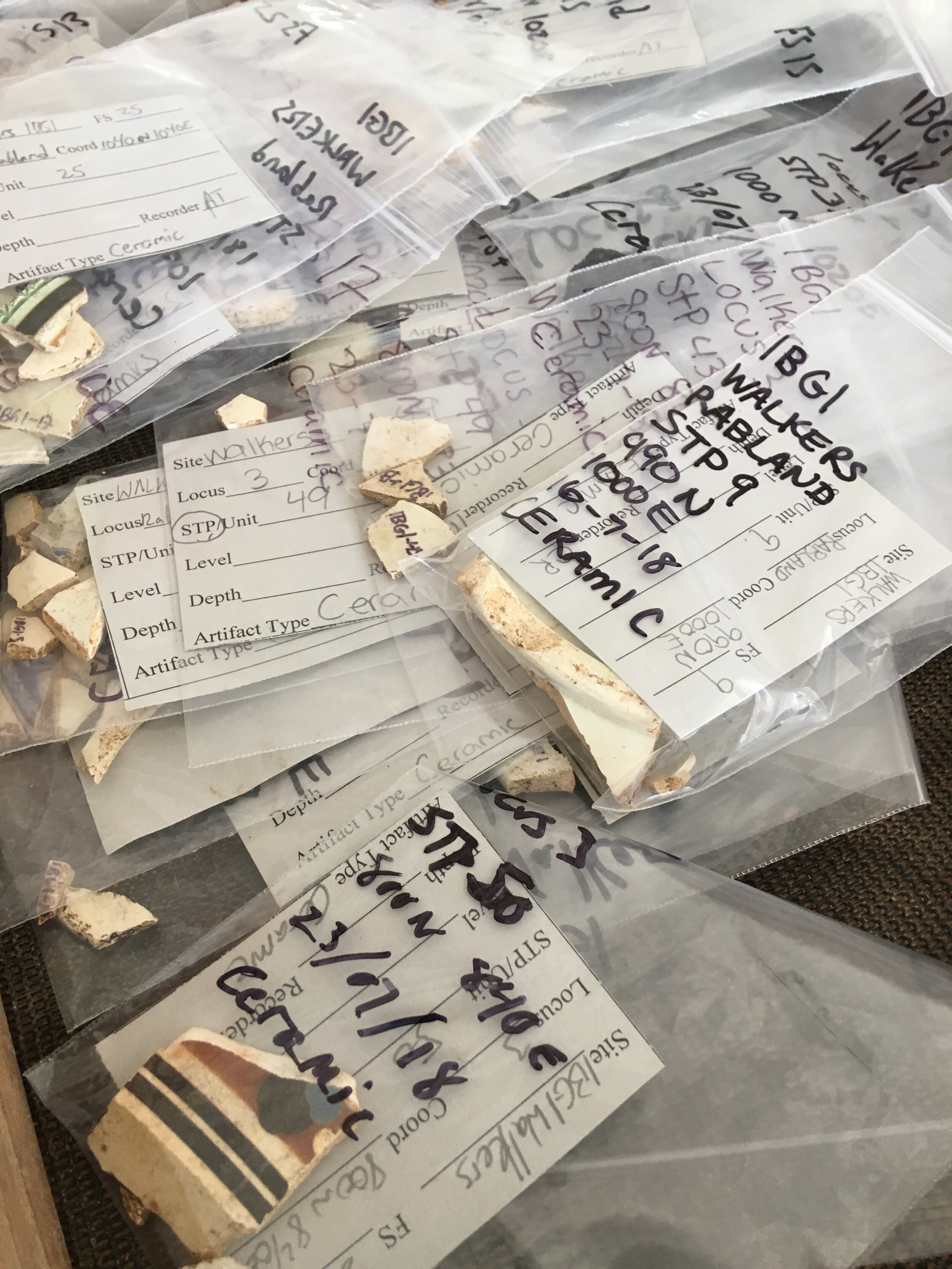

In fields surrounding the works of the plantation, test pits included household ceramics, glass bottles, construction materials, an abundance of locally-produced sugar cones, and clay tobacco pipes. However, no features, such as foundations, have yet been identified despite the recovery of nearly 3,000 household and utilitarian artifacts. Of particular note is a dense concentration of locally-produced earthenware used in the sugar production process found to the north of the plantation works (mill and boiling house). Future seasons will explore if this was an area of pottery production or perhaps a midden created when the plantation shifted to mechanized centrifugal sugar production that no-longer required the use of ceramics for drying. Surveys and analysis will continue in future field seasons, but the rediscovery of the village or other features is not necessarily the top priority of our ongoing work. In foregrounding the process of archaeology in conjunction with the experiential components of land (past, present, and future), our work also involves more creative outlets to the materiality of Caribbean plantations.

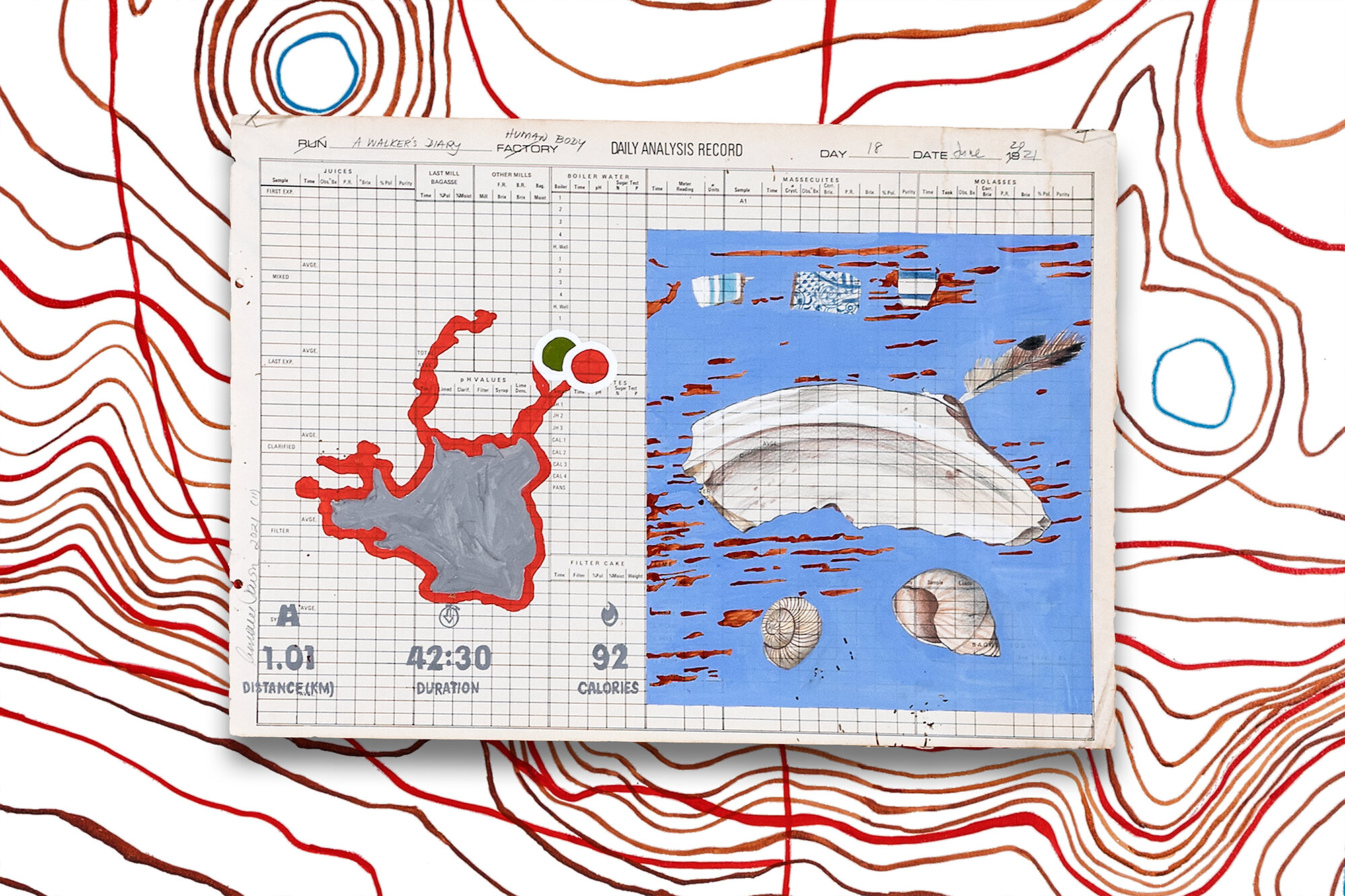

In exploring the making of race, plantation agriculture, and the relationship between Barbadians and the grounds beneath their feet, we are charting a new course for archaeological studies on the island by incorporating contemporary visual art. As a 21st-century Barbadian visual artist, Davis aims to investigate a complex place she has deep affection for, and through her contemporary art practice is asking how she might come to know a place burdened by the death machine that was the plantation. Through a critique of plantation logic, her work questions if the profound depths of any land could ever be measured or owned (Figures 3-5). New work inspired by walking the heavily mediated grounds of the plantation challenges historical renderings of the site buried beneath ceaseless cadastrals, surveys, and mappings. This work simultaneously pushes a reconsideration of an archaeological science that similarly maps and surveys through a positivistic paradigm. Importantly, her work acknowledges that these lands have their own language as layered substrates with restless histories running through them.

Figure 3: King Line, Mixed Media on Plantation Ledger Page, 2016. Photo Credit: TEOR/éTica, Costa Rica

Figures 4 and 5: A Walker’s Diary–An Effort at Disalientation, Mixed media on Daily Analysis Records on hand painted topographical map of Walkers Dairy. (Detail) 2021. Photo credit:(4) Martin Deko, Slovak National Gallery and (5) RSTUDIO

Davis’ work proposes walking as a ritual act and suggests that coursing through the landscape at dawn or dusk is one way to know a place that can complement or conflict with systematic archaeological investigations. It is during this time that Davis unearths ceramic sherds poking out of earthen tracks between fields including bits of crockery originating from potteries in the north of England that crossed the Atlantic to be used by the settler colonial class for drinking tea and serving food. Imported ceramics were similarly used by the indentured and enslaved, eventually making their way into the soil, where they were mixed with locally-made clay remains of sugar cones. These artifacts similarly comprise the archaeological assemblage collected during 2018 and 2019 surveys (Figure 6). Analysis and curation has been undertaken for the archaeological collection of nearly 3,000 artifacts, but materials collected by Davis during walks of fields and cart roads have been incorporated into vessels featured in the (bush) Tea Services exhibition (Figure 7) and “F is for Frances”, for example.

Figure 6: Washed and catalogued imported ceramics recovered from shovel test pits at Walkers Dairy in July 2018. Photo credit: Matthew C. Reilly.

Figure 7: (bush) Tea Services, Glazed Barbadian clay, 18th & 19th-century refined earthenware sherds, 2016. Made in collaboration with Barbadian master potter Hamilton Wiltshire. Photo credit: Tim Bowditch.

Repurposing these sherds collected from the surface along plantation cart roads, Davis included them in a set of tea cups, saucers and a teapot in the form of a traditional water carrier called a monkey jar. From the tea set, she serves (unsweetened) varieties of bush tea collected from the fields of the former sugarcane plantation and adjoining rab lands. Sugar-sweetened tea, a psycho-tropical sweet stimulant, provided not only a moment to pause and refresh, but a cheap tool to prolong the working capacity of the enslaved in the field. For the enslaved, many of the herbs in these bush teas also offered medical uses in bush baths, for healing, and to prevent or terminate unwanted pregnancies.

Figure 8: “F is for Frances”, Coloured pencil and acrylic on plantation ledger pages, 2016. Photo credit: Mark Doroba.

Archival evidence is similarly informing archaeological and artistic practice. For instance, the last will and testament of Thomas Applewhaite, former owner of Walkers, written in August 1816, directed that six years after his death his “little favourite Girl Slave named Frances shall be manumitted and set free from all and all manner of Servitude and slavery whatsoever.” In addition to providing insights into the lives of those who lived and labored on the plantation (as well as potential evidence of sexual exploitation/violence), the will inspired a suite that maps Frances’ name in a series of seven drawings on ledger pages (Figure 8). The letters forming her name comprise 18th-and-19th-century sherds found in the soil suggesting fragments of history understood only in part - usually through the words of the white colonial settler and most often a male voice. With Frances, along with the remains of everyday items that were used by laborers (enslaved and free), other voices become tangible, audible, and visible.

In addition to this project being a collaboration between an American archaeologist and a Barbadian visual artist, multiple institutions have contributed to the research and artwork that has been featured at exhibitions around the globe. Students from the City College of New York, the CUNY Graduate Center, Brown University, and Columbia University have participated in archaeological excavations, while Barbadian students part of the Junior Curators program at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society have visited the site to learn how excavations and artifact analysis play a role in museum curation practices. As an inclusive, collaborative project, our research doesn’t prioritize one form of engaging with material culture over another. Rather, method and theory from the worlds of archaeology, museum curation, and contemporary art all inform the ways in which the built landscape of island plantations is experienced and understood.

Investigations of the past must grapple with the fact that Caribbean soils and the vestiges of plantation life are symptomatic of fragmented postcolonial Caribbean geopolitics and traumas unhealed by the passage of time. Artists in the Caribbean have critically engaged with historic material culture in their practice (Navarro 2018), and archaeologists working in the Caribbean are beginning to explore artistic outlets through their studies (Dunnavant 2021), but it is our hope that more projects will implement a collaborative framework that recognizes the overlap in archaeological and artistic practice. Through an interdisciplinary archaeology and visual art case-study from Barbados, we suggest that material culture, though often reserved for quantitative analyses, has affective attributes that subvert positivistic readings of the plantation landscape, asserting their importance beyond what they tell us about the past.

References:

Armstrong, Douglas V. and Matthew C. Reilly. 2014. “The Archaeology of Settler Farms and Early Plantation Life in Seventeenth-Century Barbados.” Slavery & Abolition 35(3):399-417.

Dunnavant, Justin P. 2021. “Have Confidence in the Sea: Maritime Maroons and Fugitive Geographies.” Antipode 53(3):884-905.

Handler, Jerome S. 2002. “Plantation Slave Settlements in Barbados, 1650s to 1834.” In In the Shadow of the Plantation: Caribbean History and Legacy, edited by A.O. Thompson, pp. 123-161. Ian Randle Publishers: Kingston, Jamaica.

Handler, Jerome S., Michael D. Conner, Keith P. Jacobi. 1989. Searching for a Slave Cemetery in Barbados, West Indies: A Bioarchaeological and Ethnohistorical Investigation. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

Handler, Jerome S. and Frederick Lange. 1978. Plantation Slavery in Barbados: An Archaeological and Historical Investigation. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

Navarro, Tami. 2018. “Beyond the Fragments of Global Wealth.” Social Text. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/beyond-the-fragments-of-global-wealth/

Reilly, Matthew C. 2019. Archaeology below the Cliff: Race, Class, and Redlegs in Barbadian Sugar Society. University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL.